Google is currently facing anti-trust actions in many different regions. Moving first are the ones in the U.S and Australia, and EU is also following. In this project, we first read the basic background readings, do some research and take the following position for discussion:

Making a case against the current structure and practices, arguing that Google is abusing its monopoly and network power, and proposing a radical change in the platform.

This project helps us to gain a thorough understanding of digital marketing, the peculiar network and platform power inherent in this kind of marketing and the structural issues that are causing so many problems to so many businesses.

The report presents in the following format:

1. Brief synopsis of our position and argument

2. Summary of the background

- Overview of Google

- Summary of Google’s Antitrust Cases

3. Analysis

- Google’s dominance in mobile operating system market

- Dominance of Android’s default applications

- Cross-market strengths and network power

- Learning from other Antitrust cases

- Learning from emerging enforcement on data transparency and competition for fintech

4. Proposal

- Break-up of Google mobile access product/services

- Open tech standard

- Common data storage platform

5. Conclusion – Where do we go next?

- Regulators

- Industry

- Consumer

1. Brief synopsis

Recently Google has been subjected to multiple antitrust cases in many countries. Google is alleged to be abusing its monopoly and network power. In this report, a case study on Google, focusing on the mobile access segment, has been carried out. Analysis on its practices on mobile operating system, mobile apps, network effect and a few learning from other antitrust cases have revealed the following:

i. Google’s dominance in mobile operating system market

Android represents the largest market share of worldwide mobile operating system market. Google abuses its market power and uses various strategies to maintain this dominance, including (1) accessing real-time and vast amount of user data; (2) using contractual restrictions to favor its own applications; (3) acquisition of other tech companies to expand its market share.

ii. Dominance of Android’s default applications

Some default applications from Google in Android are also dominate in their markets, especially Google Search and Chrome. Google required Android handset and tablet manufacturers to pre-install the Google Search and Chrome as a condition for allowing them to offer access to its Play app store:

- As for Google Search, it represents the largest market share in search market and behaves monopolistically, including (1) data and content misappropriation; (2) giving priority to its own products and services; (3) increasing revenue by raising market access prices.

- As for Chrome, it also occupies the largest market in both mobile and desktop web browser market and behaves monopolistically, including (1) giving priority to Google’s products and services; (2) strengthening Google and hurting its competitors by setting standard unilaterally.

- Google made payments to large manufacturers and mobile network operators that agreed to exclusively pre-install the Google Search app on their devices.

iii. Cross-market strengths and network power

Google’s dominance in different markets can enforce each other and make google benefits substantially from the network effect. Google build its network among its products, like Android, Google Search and Chrome, and uses this network power to flourish its digital advertising business.

The above findings have shown that Google’s practices have indeed reinforce its market dominance gaining upper hand in abusing others in the market as well as depriving the consumers’ right to choose the preferred product or services. Therefore, changes to the practices and platform will be proposed.

2. Summary of the background

2.1 Overview of Google

Google was created in 1998 as an online search engine. One of the most important innovations in Google is PageRank algorithm which enables Google to improve the quality of its search results despite the rapidly increasing number of websites. It has been the global online search giant for years and ‘googling’ even becomes the alternative word of search.

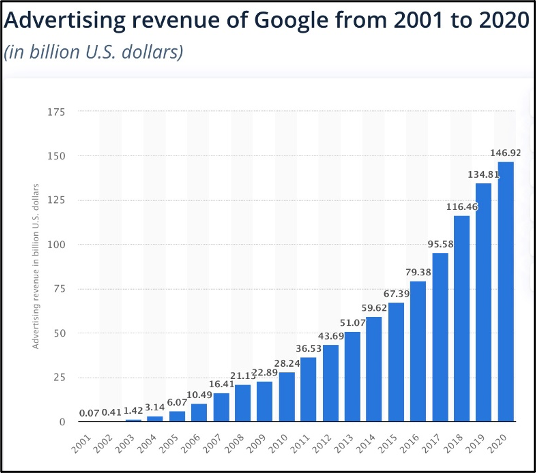

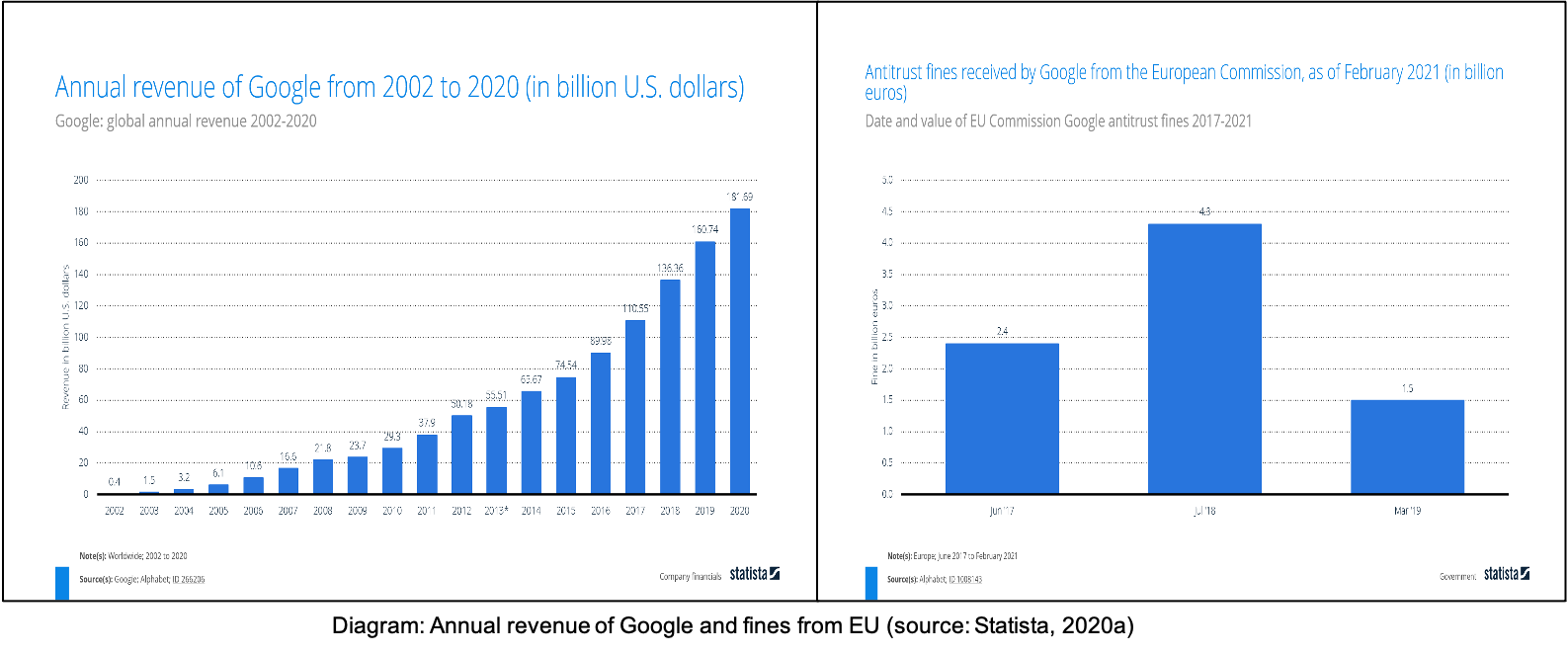

While Google has experienced continuous growth and even dominance in search, it has also diversified its services stepping into everywhere in digital industry. In 2000, Google launched its online advertising service AdWords (now called Google Ads) which allows customers to buy advertisement position on Google’s search results page by setting keywords. Google Ads has become one of Google’s core business contributing revenue amounted to 146,92 billion dollars, which represents about 81% of Google’s total revenue(181.69 billion) in 2020 (Joseph Johnson, 2021). Now Google is the largest online search engine as well as digital advertising company. It has leading edge of web browser, mobile operating system, digital maps, email, cloud computing, voice service, etc. It has more than 1 billion customers from various products including Android, Chrome, Gmail, Google Search, Google Drive, Google Maps, Google Photos, Google Play Store, YouTube, etc. (About Google, 2021). Each of them brings a huge amount of user data to Google, which enforces Google’s market dominant position and facilitate greater profitability through online advertising.

Google was restructured in 2015, setting Alphabet as the parent company and Google as a wholly owned subsidiary. Alphabet also owns the company’s non-search businesses, such as Calico, a biotech company focused on longevity (Wikipedia, 2021) , and Waymo, which is developing self-driving cars (Wikipedia, 2021).

2.2 Summary of Google’s Antitrust Cases

Google has been the subject of antitrust investigations and enforcement around the world for years. In September 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice, attorneys general from 50 US states and territories announced that they were launching antitrust investigation into this search and advertising giant. They have also alleged that Google made special deals with mobile device manufacturers to be the default search engine on their devices in order to crowd out competitors (Department of Justice, 2020). In Dec 2020, a group of 10 states accused Google of having in “false, deceptive, or misleading acts” when operating its auction system for Google Ads. And 38 states and territories alleged Google harmed competitors by favoring its own products and services when it displayed search results. (Richard Nieva & Andrew Morse, 2020).

Antitrust cases did not just happen in recent years. Nearly a decade ago, Google was probed by federal watchdogs for acting against competition — yet Google escaped the inquiry without a case in 2013 (Tony Romm, 2020).

Across the Atlantic Ocean, the UK’s Competition and Market Authority and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission had investigated Google’s dominance in digital advertising with a conclusion in July 2020, stating Google has significant market power in digital advertising where it has used its commanding power to charge 30%~40% more than Bing (Competition & Markets Authority, 2020). In 2018, the European Commission had slapped a €4.3 billion fine on Google for abusing its position with Android mobile phone operating systems on mobile devices (European Commission, 2018). Other countries have been contemplating with the move towards Google with various antitrust law.

Against the backdrop of Google antitrust allegations, we will perform a case study analyzing Google’s dominance and its impact.

3. Analysis

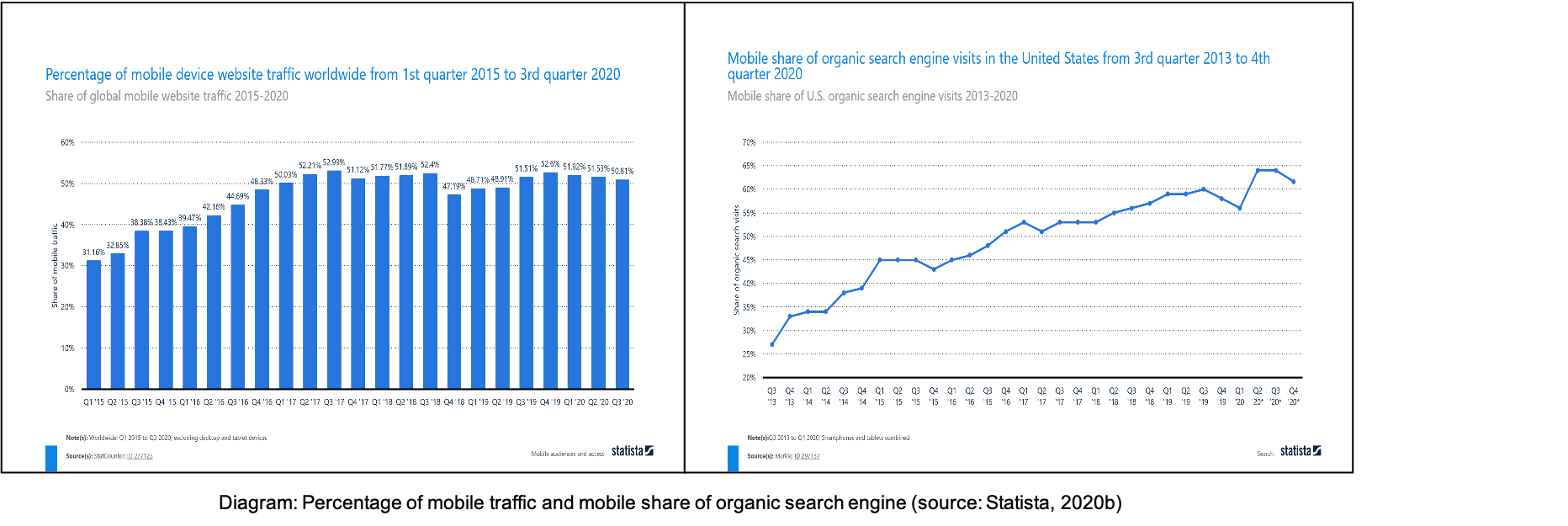

The use of mobile devices to access websites have been increasing over the years. The mobile device website traffic share has grown from 31% in early year 2015 to around 50% in year 2020 (Statista, 2020). Meanwhile the mobile share of organic search engine increased more than 2 folds from year 2013 to 62% in year 2020 (Statista, 2020).

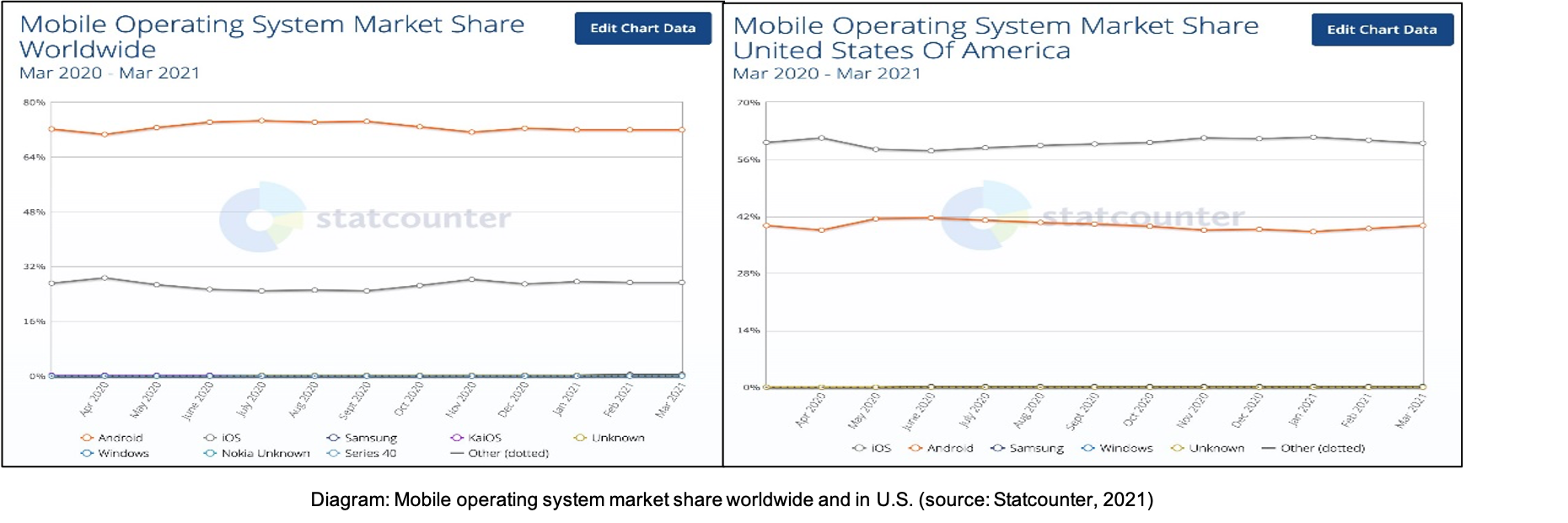

Another report from Statista (2020) has shown online shopping traffic contribution by mobile devices of more than 50%.

It is with this trend in mind that we will approach the case study on Google antitrust by focusing on the mobile segment. We will analyze Google’s dominance in the mobile industry in area of operating system, applications (apps) and mobile channel of digital marking.

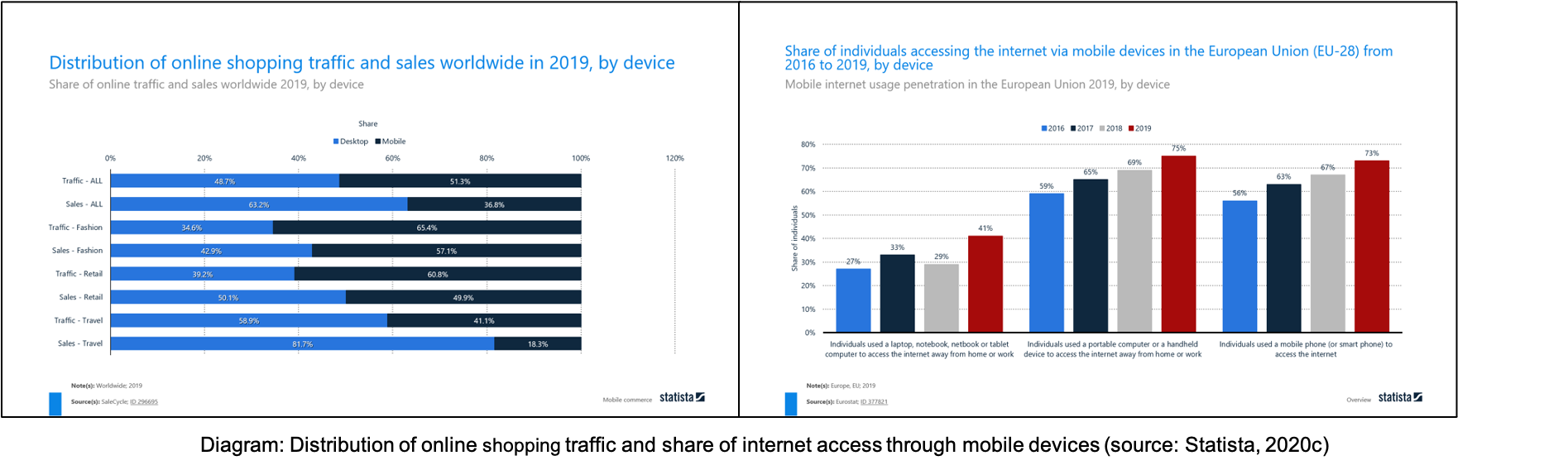

Bala & Srinivasa (2016) has provided a framework showing the mobile industry stack that is comprised of four different functional layers, where each functional layer will be depending on the lower layer. From the lens of mobile users, the browser app used will be depending on the apps installed from distribution platform like Google Play, or App Store. Whether the distribution platform is Google Play or App Store will be depending on the mobile operating system (i.e. Android, iOS), and whether the mobile device like Samsung, Apple, Huawei is adopting Android or iOS as its operating system.

Likewise, looking through the mobile industry stack from Google’s viewpoint, Google has required all the mobile device manufacturers that are using Android operating system to have Google Play or other Google key proprietary apps (e.g. Search, Maps, YouTube, and etc) pre-installed, thus giving it advantage in controlling the applications layer (Bala & Srinivasa, 2016).

Using the “Mobile Industry Slack”, we will analyze how Google builds its dominance in the top three layers, its incentives in capturing the mobile access segment, by looking into:

- Mobile operating system

- Android default applications

- Cross market strength and network

In addition, we will also use other antitrust cases or new development in technology field, i.e. fintech, as learning points in arguing our position that Google is abusing its monopoly and network power, and we will then propose for changes based on our analysis.

3.1 Google’s dominance in mobile operating system market

3.1.1 Overview of the mobile operating system market

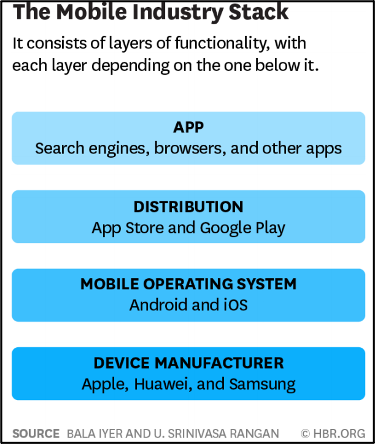

Google had acquired Android in July 2005 for about $50 million, and continue buying a suite of technologies since then, including software and hardware, to enhance its mobile ecosystem. Now Android is the dominant mobile operating system worldwide, running on about 59.98% of the world’s mobile devices in 2021. In the United States, the only alternative to Android is Apple’s iOS. Android has about 39.75% of the mobile operating system market in the United States, while Apple has about 60% (Statcounter, 2021).

Google describes Android as “a free, open-source mobile operating system” that can be downloaded and modified for free by anyone. But in reality, smartphone makers seeking to use Android must sign a license agreement with Google, which gives smartphone makers access to Google’s proprietary applications such as Gmail, YouTube, Chrome, Google Maps and Google Play Store. Moreover, Google requires certain proprietary apps to be pre-installed and placed in the prominent positions on a mobile device. Device makers must also sign an agreement which prohibits them from customizing Android. Overall, Android’s business practices reveal how Google maintains its dominant position by various contractual restrictions that impede competition. (Wikipedia, 2021)

3.1.2 Monopolistic behavior

- Accessing real-time and vast amount of user data

Android’s dominance in the mobile operating system market allows it to monitor users extensively. Android gives Google access to both user and developer data. This includes information that Google can make money from advertising, as well as strategic intelligence that allows Google to track competitors. Google’s agreements with device makers require them to configure a unique code, known as “customer ID,” so that Google can combine the metrics about the user tracked through the hardware with all the other data it collects. In addition, it requires device makers to use Google account, rather than other non-Google accounts, as user identification number to ensure that Google has wider access to user profiles (Dale Smith, 2020).

Together with Android’s extensive collection of real-time location data, Google can build sophisticated user profiles that reflect a person’s demographics, including who they are, where they go, and when and how long they use which apps, etc. These private information of billions of people are a key source of Google’s advertising advantage. Android’s data collection can thus be used to enforce Google’s dominance in digital advertising.

- Using contractual restrictions and favoring its own applications

Google invested in Android and realized it could be used to extend its dominance in search market from desktop to mobile devices. Device makers must not only install Google’s apps, but must also ensure that Google Search is the default and exclusive pre-installed Search application. In general, users tend to use default settings. This approach has enabled Google to push out competitors in mobile search and other markets. For example, Google paid Apple a large amount to ensure that it is the default search engine on iOS devices (Nick Statt, 2020).

As Android continues to gain market share, its demand grows and also the number of pre-installed Google Apps increases. We can see from the graph below that 7 of 15 most popular smartphone applications in the U.S. are from Google and 4 of them reach more than 50% of mobile audience.

Google is crowding out other applications and consuming a lot of memory on devices, stuffing users’ mobile phones with applications that they don’t need.

- Acquisition of other tech companies to expand market share

Google has a reputation for investing in start-ups to gain insights into new markets and possible disrupters. However, many of these investments ended up in conflicts and controversy when Google made use of Android’s wide outreach to flex its muscles and unfairly push its dominance into the new market.

An example is the accusation that Google unfairly under-paid artists to gain an advantage over rivals in the video streaming market. Google acquired Youtube in 2006 advancing into the video streaming market. As the default video streaming application in the Android operating system, Youtube has since become the world’s most popular music service but has been accused of making comparatively small payments to artists to give it an unfair advantage over rivals such as Spotify (Financial Times, 2016). YouTube has an estimated 1bn users and generates roughly €600m a year for the music industry. In comparison, Spotify, with a much lower clientele of just over 40 million users contributed a much higher €1.6bn a year for the music industry instead.

In a more recent case, Roku, a company which provides hardware device & software application for video streaming, accused Google of demanding preferential treatment for Youtube when Roku renegotiates its application deal on the Android platform (Yahoo news, 2021).

In conclusion, Android is the dominant mobile operating system worldwide proven by its large market share and its ability to influence the market. Google is abusing its market power and hurting is competitors by some aggressive strategies and unfair terms, and it continues expanding its market share by merger and acquisition activities. Furthermore, as we mention above, many products and services included in the default setting of Android also dominate in their markets, especially Google Search and Chrome. These products not only abuse monopoly power in their own markets, but also affect and help each other to enforce Google’s network power. Ultimately, they all contribute to Google’s digital adverting business which represents the largest part of Google’s total revenue.

In the following parts, we will analyze the dominance of Android’s default applications in their markets, including Google Search and Chrome, and its cross-market strengths to get more profits.

3.2 Dominance of Android’s default applications

3.2.1 Google Search

Overview of the search market

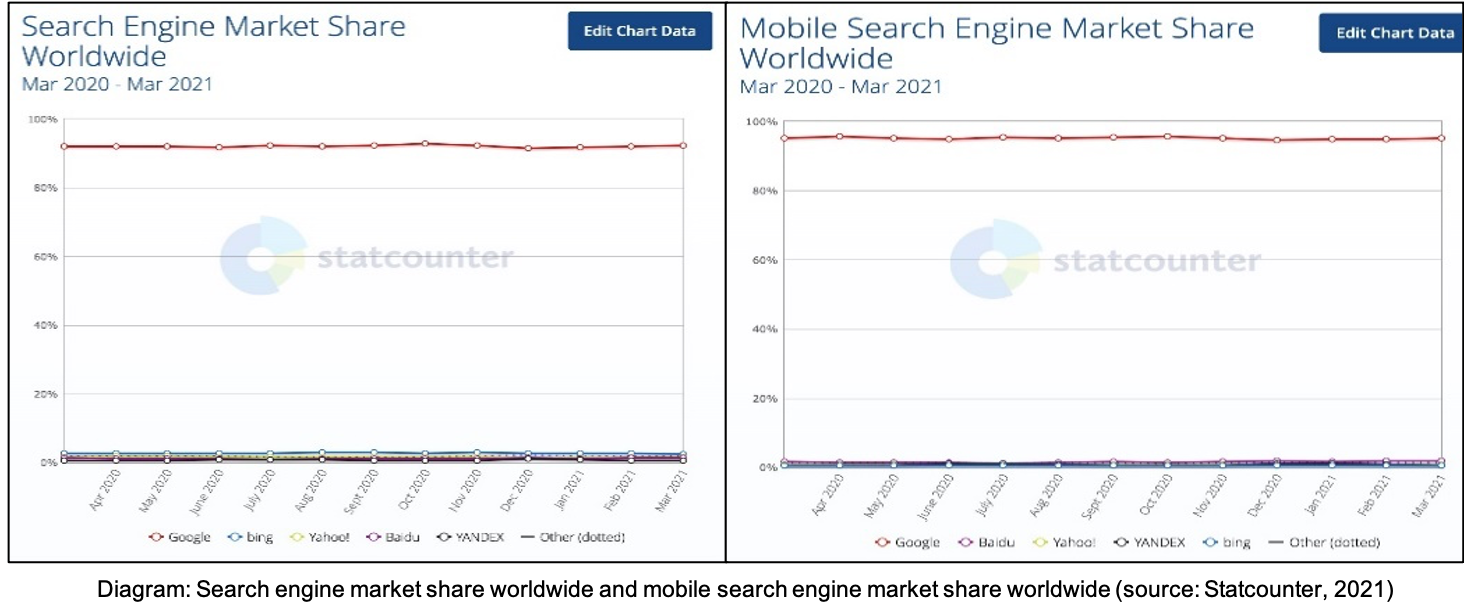

The default search engine on mobile devices with Android operating system is one of Google’s most important products - Google Search. Google has dominated the general online search market for years. From the graphs below we can see that Google maintains around 92% market share in the search engine market for all platforms and the market share is even larger in the mobile search engine market which is around 95%. Despite the significant changes in the market, such as the shift from PC to mobile, Google has maintained this dominance and its lead over its competitors for more than a decade. (Statcounter, 2021)

Google has generally facing little market entry threats in search market because economies of scale is important in this market. The high market entry cost and the advantage of self-reinforcing for the existing companies dissuade potential entrants. Even a startup with enough capital may find itself at a huge disadvantage, given that Google’s search algorithm has kept improving over the trillions of queries.

However, the appearance of vertical search engine poses a threat to Google. When Google launched in 1998, its list of search results was “Ten Blue Links,” or a set of organic results that lead users away from Google’s pages to find relevant information. Since then, Google and Bing have evolved to display blue links next to their own content and message boxes (Christopher Ratcliff, 2014). This model seems to run efficiently, until vertical search engine becomes increasingly popular. Google worries that vertical search will bypass Google Search and connect directly to users, which leads to a loss of traffic, valuable data and advertising revenue. While vertical search is a complement to Google Search in the short-term, Google is aware of the potential disintermediation and sees it as a major rival. Therefore, Google has developed various aggressive business strategies to deal with the threats and maintain its dominance in the search market, benefiting from the economies of scale and self-reinforcing data.

Monopolistic behavior

- Data and content misappropriation

In year 2005, Google started to build its own vertical search service by partly pulling content directly from third-party providers. During the process, Google used its dominance position in the search market to ask third parties to allow Google access to their content, otherwise they will be completely removed from Google search results. In addition, Google also intercepted traffic from third-party websites by forcibly scraping their content and placing them directly on Google’s own pages. (Jerrold Nadler & David N.Cicilline, 2020)

In this way, Google extracts value from third parties without their consent. Due to its dominance, these third parties have little choice but to allow Google’s misappropriation to continue, stealing content and getting a free ride on the innovation of others.

- Giving priority to its own products and services

In 2007, Google launched Universal Search, which aims to provide users with search results that integrate Google’s various professional services, including Google Images, Google Local, and Google News (Danny Sullivan, 2007). Universal Search is designed to improve users’ search experience and drive traffic to Google’s own products, regardless of whether those products are the best or most relevant for users. Google adjusted its search algorithm to automatically rank some of its own products above its competitors. In addition to this, Google also imposes algorithmic penalties, which automatically downgrades some of its competitors. This double blow has put its competitors at a disadvantage. Given that the probability of a user clicking on a piece of content drops sharply along with the ranking, competitors’ traffic decreases dramatically. At the same time, Google’s self-preference comes at the expense of users’ benefits since they are not shown with the best search results.

This action benefits Google in two aspects. First, Google shifts more traffic and business to their own products. Second, competitors suffered from algorithmic penalties may have to pay more to get a better search position, which contributes to an increase in advertising revenue for Google.

- Increasing revenue by raising market access prices

Google used some tactics to raise market access prices while reducing search results quality. In 2000, Google launched AdWords (now rename as Google Ads), which allows advertisers to pay for the keywords that makes ads appear on the right side of Google search results page. Since then, Google has changed the way ads displayed on its search results page, increasing the number of ads placed above organic search results and blurring the distinction between advertisement and the way organic search results are shown. In 2016, Google introduced a redesigned page that removed ads on the right side and added one more Ad position at the top of the organic search results and three Ad positions at the bottom of the page (Christopher Ratcliff, 2016). The effect of this change is to push the organic search results further down, requiring users to scroll down further to reach the unpaid results.

One result of these changes is that users are clicking fewer organic search results. For companies that rely on Google Search to acquire users, these changes lead to a higher advertising fee since they are not able to get enough traffic only by organic search. When search results are no longer presented based on their quality, these companies are no longer competing for users by providing high-quality webpages and services, but by how much they pay Google. It clearly shows that Google is abusing its market power and is not constrained by its competitors in the search and digital advertising market.

3.2.2 Google Chrome

Overview of the web browser market

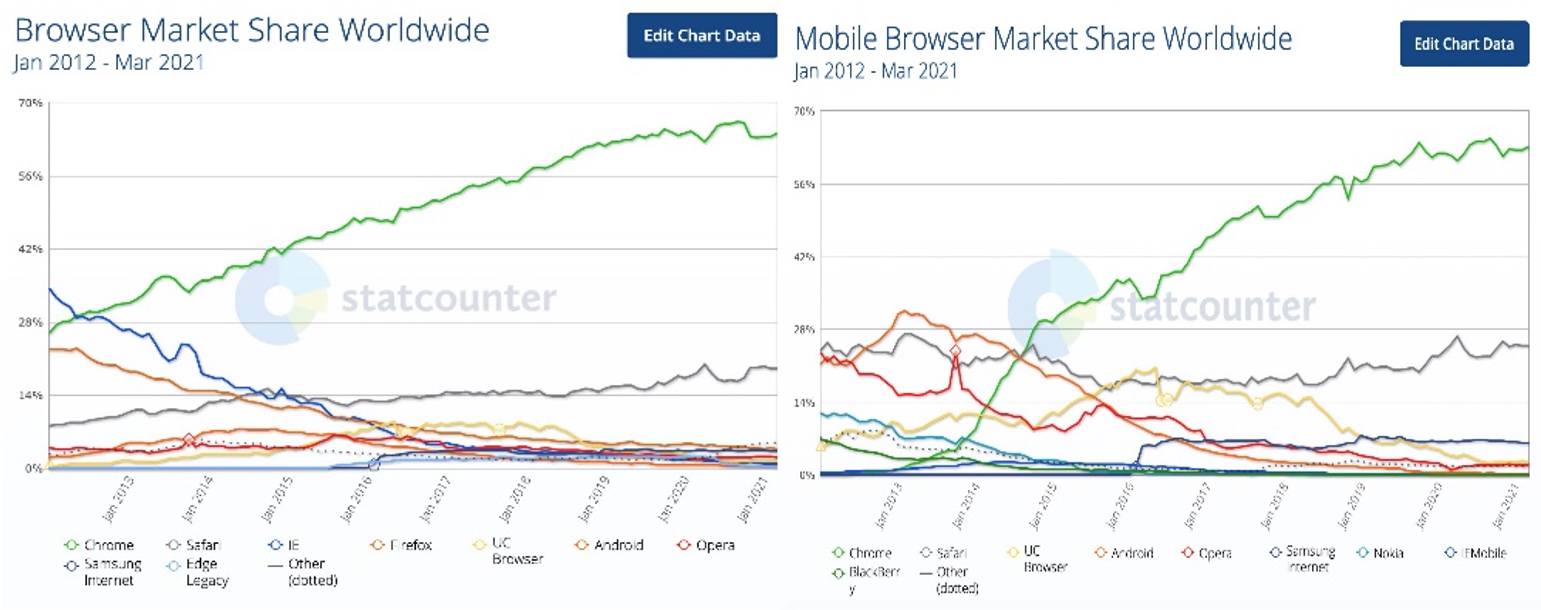

Chrome has been the leading web browser since 2012. It accounts for about 63% of mobile browser usage as well as about 65% of usage for all platforms worldwide. (Statcounter, 2021).

There are several strategies that help Google to keep its dominance in web browser market. First, as we explained above, Google has made Chrome the default browser on most Android devices. Second, Chrome has benefited from network effects. Web developers design and develop for Chrome because it has the largest number of users, and users are attracted to Chrome because their pages work well on Chrome. Third, Google uses its popular applications to support Chrome. Specifically, Google focuses on improving Chrome’s features to provide a better experience with applications like YouTube and Google Search. This is an advantage that other browsers don’t have.

Google uses its market power and its control of the Android operating system to expand its market share in browser market. And Chrome’s dominance gives it an important power as a “gatekeeper” in managing and monitoring user activities.

Monopolistic behavior

- Giving priority to Google’s products and services

Google can leverage its dominance to support its own products and services through design choices and default settings. For instance, shortly after Chrome’s release, Google began promoting it in many ways, including placing a link in the top corner of its search homepage and buying AdWords ads for Chrome. (Alex Chitu, 2008). This strategy significantly drove Chrome’s growth. In 2010, the market share of Chrome reached about 14%. And this growth trend flattened in 2012 when Google stopped the promotion strategy (Statcounter, 2012). In addition, Google strengthened its market power in the browser market by setting Chrome as the default web browser in Android system. If users switch to another search engine, Google will prompt users to change their default search engine back to Google Search and most users are very confused by this prompt and often click “Restore Settings”. In this way, Google makes its competitors lose a lot of users.

- Strengthening Google and hurting its competitors by setting standard unilaterally

One of Google’s latest actions is that third-party cookies will no longer allowed in Chrome by 2022. By removing third-party cookies and restricting third-party advertising service, Google can benefit by enhancing its dominant position. After this change, Google itself can still track users relying on its entire business ecosystem, while it will hurt its competitors by getting more advertisers to turn to Google. (Eerke Boiten, 2021)

Overall, Google establish its dominant position in the web browser market by abusing its market power in search, mobile operating system and digital marketing. Its market dominance has forced out potential competitors in the market, leaving little choice for users (ads, apps) and deprive users’ right to choose their preferred product.

3.3 Cross-market strengths and network power

Network effect is described as a product/service/technology is improved and becomes more valuable when more people use it, and a higher quality will lead to a larger number of people using this product/service/technology. As we already explained above, Google’s dominance in different markets can help and reinforce each other and make google benefits substantially from the network effect.

- Google’s business network

Android’s dominance in mobile operating system helps to enforce the dominance of Google Search in search market and the dominance of Chrome in web browser market. In return, Google’s monopoly power in search market helps to promote Android and Chrome. And Chrome builds a digital platform for Google to manage its products and services. The interaction across different markets build a huge network for Google, which making it defensible in the digital industry.

- Network power in digital advertising market

Most importantly, the network power effectively serves Google advertising business. Google is building its business ecosystem, including Android, Google Search and Chrome, to assemble user data sets and create user profiles, and ultimately drive advertising revenue. Google’s dominance gives it a strong grip on the digital advertising market. Advertising revenue of Google increases dramatically from 2001 to 2020. And according to Google Ads statistics, 73% of the paid search market share belongs to Google and 63% of people have clicked on a Google ad. Many companies spend the majority of their advertising budgets on Google. (Sarah Berry, 2019)

3.4 Learning from other Antitrust case

- Learning from Microsoft Antitrust case

Looking into previous antitrust case on another tech-giant has offered us insight into possible solutions. With the conclusion of antitrust case settlement with the Europe’s competition commissioner in 2009, Microsoft have made all its Windows version in the European market to come with a “choice screen” instead of a default pre-installed Internet Explorer for the users to choose (The Economist, 2009). In addition, the Commission has also requested Microsoft to open up their code for Windows for server manufacturers to design network computers that could adapt to Windows operating software. The settlement case has essentially ‘break-up’ Windows package offering, instead of the company business itself, so that the PC-makers and the customers can decide freely on specific packages that they need (The Economist, 2004). If the similar approach could be taken studying the Microsoft antitrust case, the possible break-up of Google product services offering (i.e. unbundling of Android Operating System from Chrome) and the opening of code sharing of operating system to enable other system users to design and connect smoothly.

- Learning from Visa case

In a recent high-profile case of an antitrust lawsuit, the US DOJ blocked Visa from acquiring the payment platform company – Plaid, accusing Visa of trying to eliminate a potential competitor with the deal. With online payment services becoming more common place during COVID-19 pandemic, Plaid provided the much-needed software platform for applications to connect to customer’s banking account. Nevertheless, its fast technology advances pose a threat to VISA because the dominance of such payment platform might entice consumers to pay directly via their banking account rather than via a debit/ credit card. Although Visa argued that Plaid will complement rather than threaten its existing business, the deal was eventually blocked on antitrust grounds (Financial time, 2021).

We can observe similarity of Microsoft (and Google) antitrust case here, where the defendant would claim that any acquisition (e.g. Microsoft acquiring Netscape) proposal would bring complimentary and improved efficiency to the current business product, rather than a hostile anti-competition approach. If Google maintain its current practice and pursue the same argument against the antitrust allegations or lawsuits, it remains a risk to Google of going to the same path and similar outcome like Visa or Microsoft, although the final decision will still be pending on the intelligence and judgment by the relevant authorities and courts. Even though the current fines by European Commission had been only a small fraction (1~3.2%) of Google’s annual revenue, Google will definitely look at the overall cost (e.g. fines, legal cost, lobbying cost, reputation) in the long run, with increasing antitrust attention received in other countries worldwide.

3.5 Learning from emerging enforcement on data transparency and competition for fintech

- Learning from Payment Services Directive (PSD2) – an open banking standard in EU

The EU Opening banking standard - PSD2 standard was introduced in 2018 to maintain competition in the banking sector and continue innovation in the Fintech world while ensuring customer data security. As PSD2 take on the big banks which had been traditionally labelled as ‘too big to fail’, we will attempt to take some learning points from this open banking standards and apply them to our big Tech ‘gatekeepers’ such as Google.

The open banking standard - PSD2 require that banks provide qualified payment service providers (PSPs) connections to client accounts to initiate payments. The key pillars of PSD2 are to firstly ensure transparency with non-discriminatory charges for both consumers and the PSPs. Secondly, protect consumer’s data with strong security requirement. Lastly, PSD2 also dictate the technological standards by which banks must allow other PSPs to connect with their systems to access account information and initiate payments on behalf of customers. These standards also require banks to provide a protected “sandbox” to PSPs for testing ongoing development of services that use the bank’s interface. (McKinsey & Company, 2018)

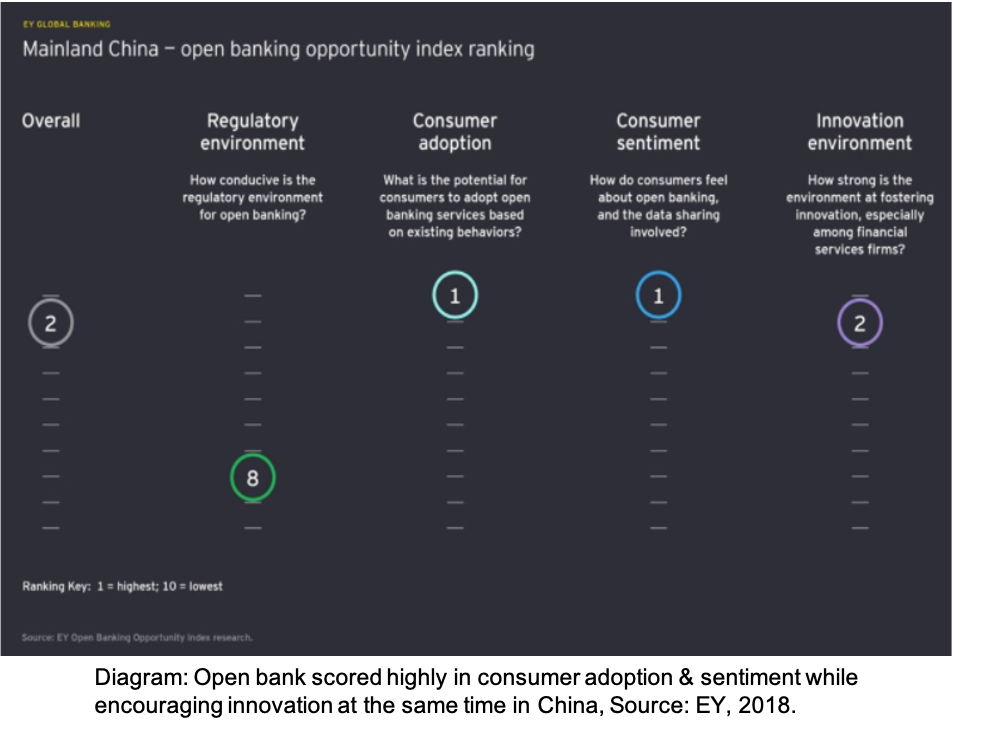

Although it is too early to determine if open banking has been a success in EU, we already saw that open banking achieved substantial success in China, driven by an economy which is innovation focused and consumers who are digitally connected. (EY, 2018)

4. Proposal

From the above analysis, it is clear that Google’s current practice has reinforce its market dominance and created unfair competition in the mobile access segment. Changes will need to be implemented, with proposal as followed:

4.1 Break-up of Google mobile access product/services

Learning from the Microsoft antitrust case in Europe, we can see that one possible change to Google in settling the antitrust cases could be a break-up of its current product or services.

- Stop the compulsory agreement with Android handset manufacturers on any pre-install Google apps

While critics of antitrust case have claimed that it is a fair market with willing-seller and willing-buyer between two contracting parties (Google and the mobile device manufacturers) agreeing to the current term to pre-install Google proprietary apps together with Android operating system; the same could be argued that it is unfair to the mobile device users depriving their choice to have Google apps pre-installed rather than their preferred apps. Going through the Mobile Industry Stack by Bala & Srivinasa (2016), stopping the current contract practice of bundling the Google apps together with Android mobile operating system would instead enhance the functionality layer of ‘Distribution’, which is Google Play. Mobile users will have their preference to install any apps that are available in Google Play at will. While some had argued that provision of pre-installed Google apps would lower down transaction cost and eliminate users’ time to install apps (Bork & Sidak, 2012), any pre-installed apps would have occupied the device memory storage space, thus reducing the actual storage space that reach user’s hand. Therefore, mobile device users are not getting full value of the storage capacity from the manufacturers, and sometimes have to incur extra cost for adding new storage space. This cost, however, is often excluded by antitrust critics.

Breaking up this pre-installation apps, not only extra storage capacity could be saved (and instead transfer the installation choice to user), there will be increase level playing field in the functionality layer of ‘Distribution’ and motivate app developers to offer more memory-efficient and effective solutions to mobile users.

Consequently, installation of Google proprietary apps by users by choice would provide a strong argument to Google to defend themselves against antitrust case, as their dominance (if Google proprietary apps like Google Search, Google Map, etc have maintain as the preferred choice) in the market are determined by the customers, and not by built-in contractual advantage with the mobile device manufacturers.

- Introducing ‘Opt-in’ feature, instead of ‘Opt-out’ feature in Google apps

Other than the break-up between Android mobile operating system and pre-installation apps, another feature could be introduced to Google proprietary apps, for users to ‘opt-in’ extra features, instead of the current normal practice of ‘opt-out’ selection. For example, if users would like to receive advertisement when they do search using Google Search or Chrome, they would have to select ‘opt-in’ in the browser setting to have advertisement appear together. Users of Google Ads, will have to ‘opt-in’ for their advertisement appearing in Google Network Partners (like YouTube) in order to gain extra ad appearance through multiple channels, instead of the current default setting where the user will have to untick and select ‘opt-out’ of those additional features. Again, it is giving the right to user for a conscious choice. It is the same case like ordering fool when reading a menu in restaurant. Both set meals, and a la carte appear with their prices in the menu for the customer to choose; rather than having a default meal sets for diners to opt-out individual meal, making a difficult thinking situation for the diners.

4.2 Open tech standard

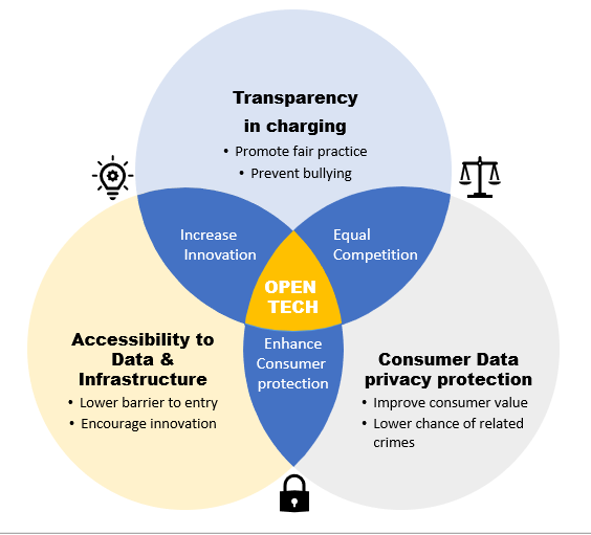

To address the thorny issues posed by our big tech ‘gatekeepers’, we believe that the existing antitrust laws which are punitive in nature are not sufficient. An active preventive/ nurturing approach must be used to address these issues holistically instead. Thus, we will model against regulations like the Open bank PSD2 standard to propose a set of governing principles so that big techs like Google take active steps to ensure their platform is compatible with smaller rivals and share data with these rivals without compromising the user’s data security. We will coin our proposed approach the ‘Open tech’ standard.

Our major pillars for the Open tech standard are largely modelled against the EU PSD2 standard for the banks. (see diagram below)

Our first pillar is to ensure transparency and non-discriminatory charges for 3rd party applications to use Google’s mobile suite of services (e.g. Android, Google Ad etc.). The aim of this pillar is to overcome the possibility that Google is making use of its huge market share to make unfair demands to 3rd party applications.

Our second pillar is to protect user’s data with strong security requirement. The aim of this pillar is to ensure that big Tech like Google invest in the platform to ensure user’s data are protected and processes and infrastructure are in place to ensure secure sharing of data with only qualified 3rd party applications.

Our last pillar is to define technology standards which big tech must adopt to allow other qualified 3rd party applications to connect with Google’s systems to access consumer’s data. This could possibly be achieved via open API which provides rivals more reach into Google’s infrastructure and data. If successful, such a measure lowers the barrier of entry for start-ups looking into entering the space while ensuring user’s data are protected at the same time. This proposal is also similar in spirit to EU’s proposal to enact laws and regulations to prevent big tech companies like Google from participating in ‘unfair practices. Such ‘unfair practices’ range from favoring their own services to their refusal to work with competing ones. (The Economist, 2020).

Given Open bank’s widespread success in countries like China (see diagram below), we are confident that a similar holistic regulatory framework like Open tech can work as it lower the barrier of entry and encourages competition and innovation from smaller firms while protecting user’s data at the same time.

4.3 Common data storage platform

The collection and control of user data is one of the most important source of Google’s market power. It becomes more and more powerful with an increase of data collection. With the user data, Google can build sophisticated user profiles, which benefits the development of its products and services and make more profits. From the analysis part above we also can see that Google is trying to acquire as much user data as it can.

Data even become one of the most valuable property in the digital companies. But it is not very appropriate to keep this data as the private property of these companies. First, the user data often includes private information which is widely misused by these companies. Second, in the process of collecting the user data, there are improper or even illegal behaviors which violates data security and private information protection. Last but not least, as the largest contributor to user data, we don’t get anything in return. Digital companies use data created by us for free to enforce their network and make immense profits.

Therefore, it may be more appropriately to store all the data in a common platform and digital companies can bid to use them. In this way, data can be stored safely under supervision. Moreover, when these tech giants no longer possess a huge amount of data and they have to pay for using data, their monopoly power and network power can be significantly weakened. Nevertheless, we recognize that setting up such a common platform for data storage will face tremendous implementation difficulty, especially when each country has its own set of data privacy protection law. However, if done correctly and successfully, the competition among tech companies will no longer be about data volumes, but about algorithms to improve the data usage efficiency, which is more meaningful.

5. Conclusion – Where do we go next?

We believe Google should re-focus its purpose to generate not only shareholder value but also positive society impact. A monopolistic big tech ‘gatekeeper’ known for its unruly behaviour of bullying its competitors and crowding out competition does not look likely to last the race in the long run. In a recent survey by BCG (BCG, 2018), although 83% of employees in big tech companies says their company ‘live purpose with passion’, only 3% of Americans believe that big tech companies can be trusted to do the right thing. This strong disconnect between the big tech companies and the general population is reflective of the urgent need for big tech to start shifting focus away from solely creating shareholder value. To win the race in the long run, Google must start focusing on customers, employee, and community and how they can bring value to them.

- Regulators

Next, regulators all over the world should start investing in regulations and framework to guide the rapid growth of the technology industry. Google’s 2020 net revenue of $147 billion far exceeded the $44.6 billion made by 1 of US’s biggest bank Goldman Sach. Although much larger in size and in possession of vast amount of user data, the tech industry is nowhere as regulated as the banking sector. The existing antitrust laws are largely punitive in nature and hardly constitutes a framework to nurture a tech ecosystem which has grown rapidly in the last 2 decades. There is thus an urgent need for regulators all over the world to collaborate and setup framework to regulate this industry. In addition, effective implementation of such a digital framework would contribute to the country’s economy and increase its share of the digital economy, thus providing variation of revenue streams.

- Industry

Antitrust case against Google and the likes should bring the industry together in reviewing the current practices against the backdrop of increasing demand from both the consumers and the regulators. Apart from accusing each other in antitrust case, the industry players could do more in introducing convincing measures to both the regulators and the consumers in allaying their fear of either antitrust, data privacy or collusion in market. The rising of ad-blocker apps serve as a wake-up call to search engine developer, that there is such a demand by consumers. Google’s recent call to discontinue third-party cookies in Chrome by year 2022 is another response to increasing concern from internet users. More proactive measures should have come to response to stakeholders demand instead of being left to the authorities to fix the market.

- Consumer

Lastly, consumers should start taking active steps to lobby for greater transparency and standards in personal data usage. Although consumers in general care about privacy, a survey from Redman & Waitman (2020) showed that only 32% of such consumers are willing to act to protect their privacy. (e.g. switch providers over data sharing policies). Such complacency might be precisely the reason for the lack of motivation of the big tech companies to improve their data governing and sharing standards.

Reference

Please check here.